Global Genetics Study of Skin Colour Unearths 14 New Genetic Markers

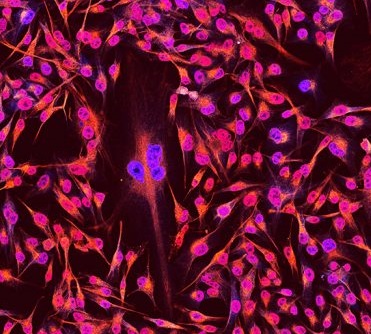

Melanoma Cells (Image: QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute)

Scientists have doubled the number of genetic markers known to influence the ability of a person’s skin to tan.

Researchers from QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute took part in the major international study, which collected data from 176,678 people with European ancestry.

The findings were published today in Nature Communications.

Associate Professor David Duffy from QIMR Berghofer’s Genetic Epidemiology Laboratory, said the study found 14 new genetic variants that predisposed people of European heritage to tan more darkly after exposure to the sun.

He said 10 of those genetic markers had never previously been identified as having an impact on skin, hair or eye colour.

“The skin’s tendency to burn rather than tan is a major risk factor for skin cancer and melanoma,” Associate Professor Duffy said.

“By identifying the genetic variants responsible for determining whether we tan or not, we can potentially identify new targets for treating skin cancer and melanoma in the future.

“One of the most interesting features is that we were already studying two of these new genes for risk of melanoma but we did not know they also influenced skin colour.”

Associate Professor Duffy said the research also confirmed six previously identified genetic markers that influence a person’s ability to tan rather than sunburn.

He said they were previously known to be involved in the production of the skin pigment melanin.

“Seven of the new genetic markers are also involved in the production of melanin, so it is not surprising these genetic variants may influence skin colour,” Associate Professor Duffy said.

“Now that we have identified these markers that influence skin colour, we may be able to assess whether and to what degree they play a role in determining a person’s risk of developing skin cancer.”

The study used data from more than 5000 Australian twins and their families who took part in QIMR Berghofer’s Q-Twin study, which started in 1990.

It also used data from 121,296 individuals of European ancestry from the UK Biobank.

Associate Professor Duffy said the findings would be important in better predicting an individual’s risk of developing skin cancer and melanoma.

“In earlier work, we have shown that if you have darker skin but you are carrying light skin colour genes, your risk of melanoma is closer to people with lighter skin,” he said.

He said the findings also provided insights into the genetic basis of evolution of skin colour.

“The further early humans moved away from the equator, the lighter their skin colour became,” Associate Professor Duffy said.

“This is a change likely driven by the difficulty of making Vitamin D in the skin when sunlight is less intense.”

The study was a collaboration between multiple international research bodies, including King’s College London, the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Florida and the Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

The findings were published in Nature Communications.