Researchers develop new test to help fight deadly melanoma

Researchers from QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute have developed a prototype test that can help identify if patients with deadly metastasised melanoma are likely to benefit from immunotherapy.

Details about the test and the study have been published in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

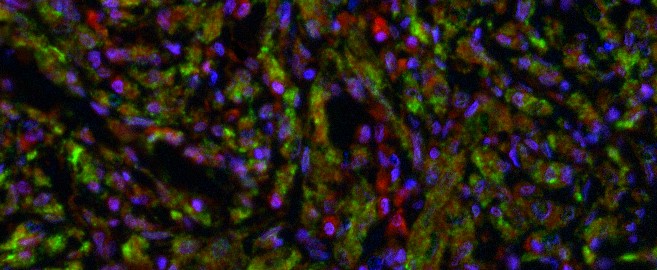

The prototype test detects levels of the protein LC3B on cancer cells. High levels of LC3B are associated with better patient responses to a form of treatment known as checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy.

Metastatic melanoma is a very aggressive disease and according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 1,375 Australians died from it in 2020.

Most patients undergo surgery and almost all patients with metastatic melanoma are now given immunotherapy as a standard frontline treatment.

Lead researcher Associate Professor Jason Lee, who heads QIMR Berghofer’s Epigenetics and Disease group, said immunotherapies have remarkably improved treatment and survival rates for metastatic melanoma, but more than half of all patients do not respond.

“We need to treat these patients quickly and with the correct kinds of drugs to have any success,” Associate Professor Lee said.

“Our study found patients with high levels of LC3B in their tumour cells had significantly longer survival due to better responses to immunotherapy treatment than those with lower levels. The study showed 95 per cent of patients with high LC3B levels were alive after 3 years, compared to 60 per cent of patients with low LC3B levels.”

The researchers used tumour and blood samples collected from melanoma patients before and after treatment to get a better understanding of the role of the LC3B protein in metastatic melanoma and to develop the prototype test.

PhD candidate in QIMR Berghofer’s Epigenetics and Disease group, Greg Kelly, said they also identified that patients with metastatic melanoma had very high levels of the epigenetic enzyme G9a – which acts on LC3B protein.

“The enzyme G9a acts like a traffic jam, reducing the ability of cancer fighting immune cells to reach the tumour,” Mr Kelly said.

“Building on the group’s previous work, we explored how targeting the G9a enzyme could help in the fight against melanoma. Our lab experiments showed inhibiting the G9a enzyme led to higher levels of LC3B proteins so the immune system could re-engage in the fight against melanoma both on its own, and in combination with immunotherapy.”

Associate Professor Lee said the findings provided hope of new treatment options in the future.

“We are now also working to develop a drug that can effectively inhibit the G9a enzyme,” Associate Professor Lee said.

“We believe blocking the activity of G9a enzymes will in turn raise the level of LC3B protein, making patients more responsive to immunotherapy and possibly even other treatments.

“We are actively working to develop a drug that can be used to treat patients, but this will take time.”

Associate Professor Lee said the researchers plan to expand the study using a larger set of patient samples to test the robustness of the prototype test to predict immunotherapy resistance.

The current study was partly funded by the Queensland Emory Development Fund and the Australian Skin and Skin Cancer Centre.

The study findings can be accessed on the Clinical Cancer Research website.

Media: Gail Burke + 61 427 179 216; Gail.Burke@QIMRBerghofer.edu.au.